Reenacting Reality: The Unique Visual Style of Lance Oppenheim’s Ren Faire

By: Ellie Powers

When I last spoke with Director Lance Oppenheim, he had just released his feature-length documentary for FX, Spermworld. Over the course of our first conversation, Lance dissected his exploration of the territory where reality and fiction meet using the tools of narrative and documentary filmmaking to best shed light on previously unseen cross-sections of our world.

What Lance began with Spermworld, he expounds on in his HBO Original documentary series, Ren Faire, centering on the succession crisis for the largest Renaissance festival in the world, just outside of Houston, TX and its eccentric creator, George Coulam. He describes the project as a miniature portrait of the American Empire at our current moment in history. With the series, Lance experiments with orchestrating real life to dramatic crescendos. Along with Cinematographer Nate Hurtsellers and Colorist Damien Vandercruyssen, Lance sought to create a look as unique as his style of storytelling.

Lance recalls searching for references to illustrate what he was after and coming up empty, eventually riffing to arrive at an “old Hollywood swords and sandals feeling but a contemporary pastiche version of it.” To achieve this, Hurtsellers used Panavision anamorphic lenses and incorporated Steadicam tracking shots through the festival to add to the feeling that this isn’t your typical documentary. Lance deemed the goal to create a Ridley Scott Kingdom of Heaven styled movie. “It's just massive, epic. This is a period piece,” he explains.

Ren Faire was Lance’s third collaboration with Vandercruyssen (first being Some Kind of Heaven, and second, Spermworld), and they have developed a unique look from digital photography that leans into a filmic look, but not just an imitation of 35 mm. Instead, they strive for “a new sort of image that both feels digital and filmic and in some ways that represents what we're trying to do with the story.”

Evoking God’s Light & A Rococo Style

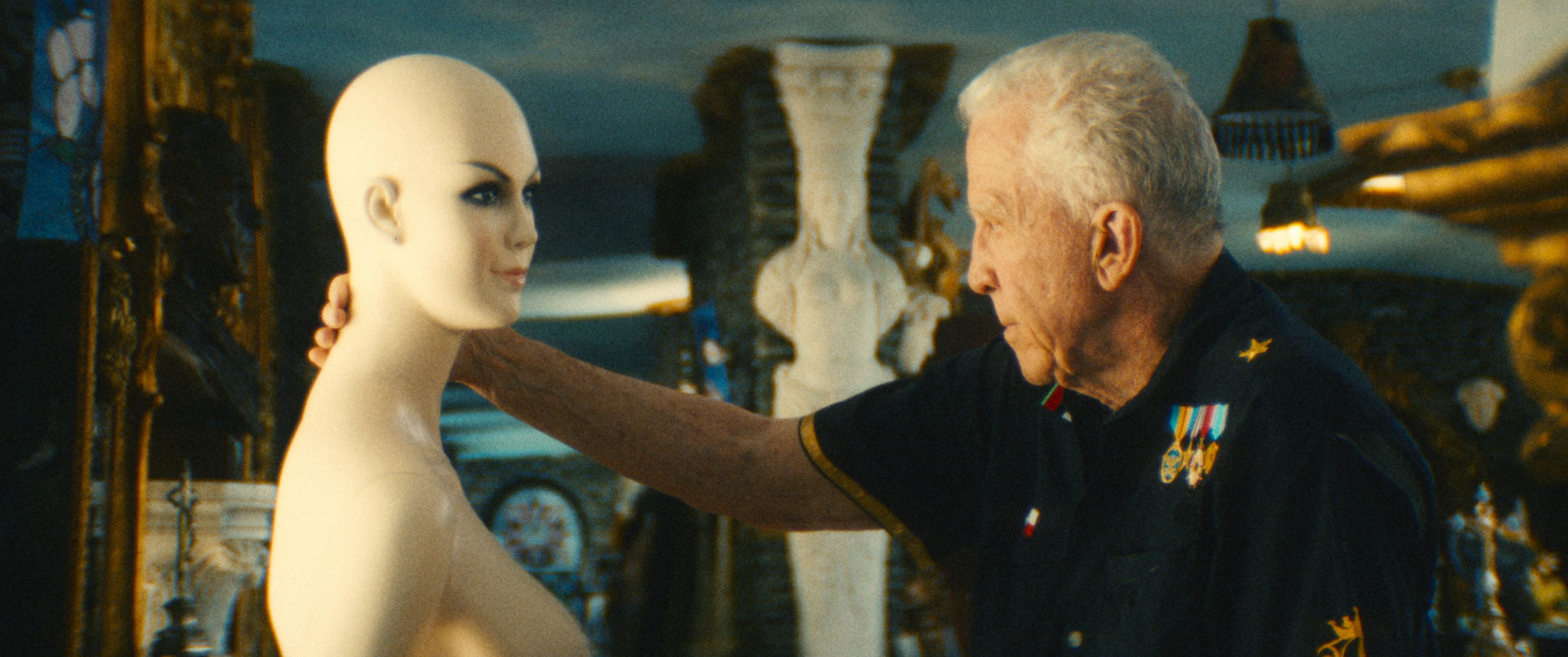

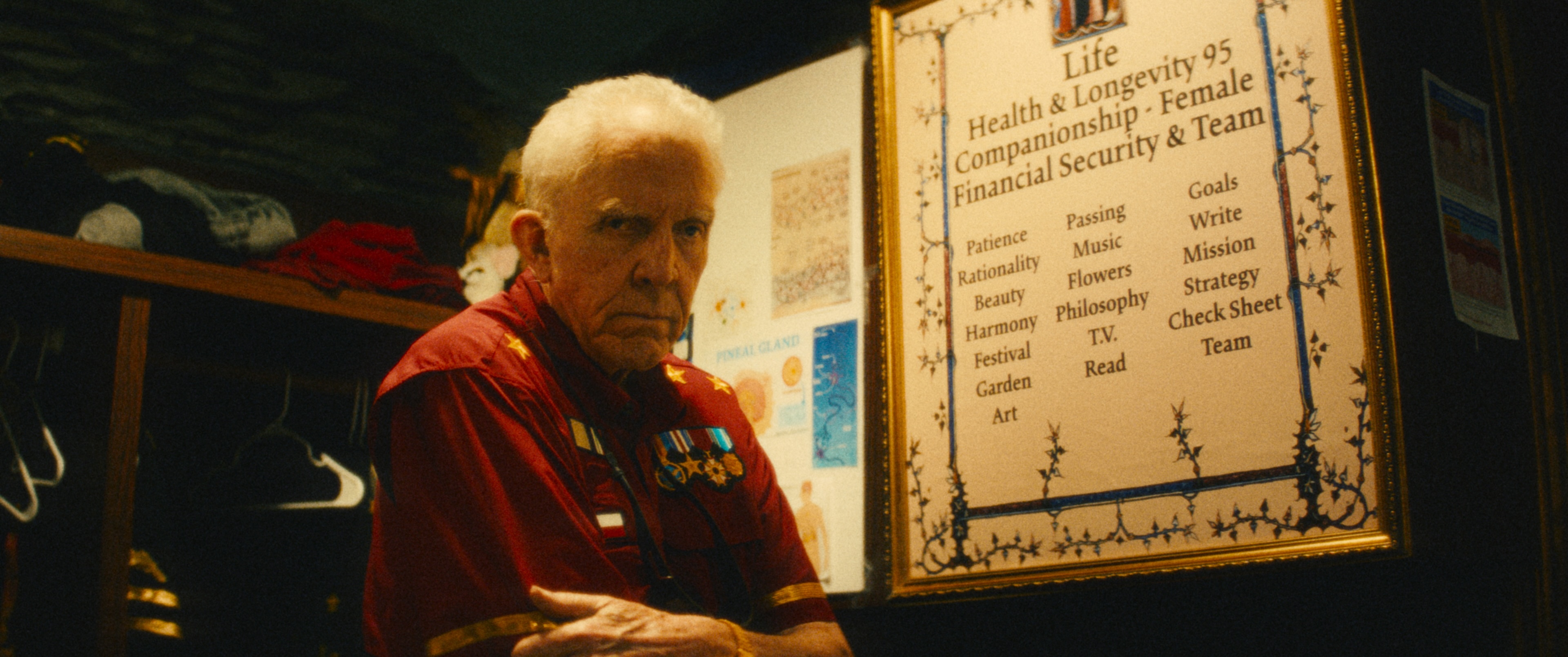

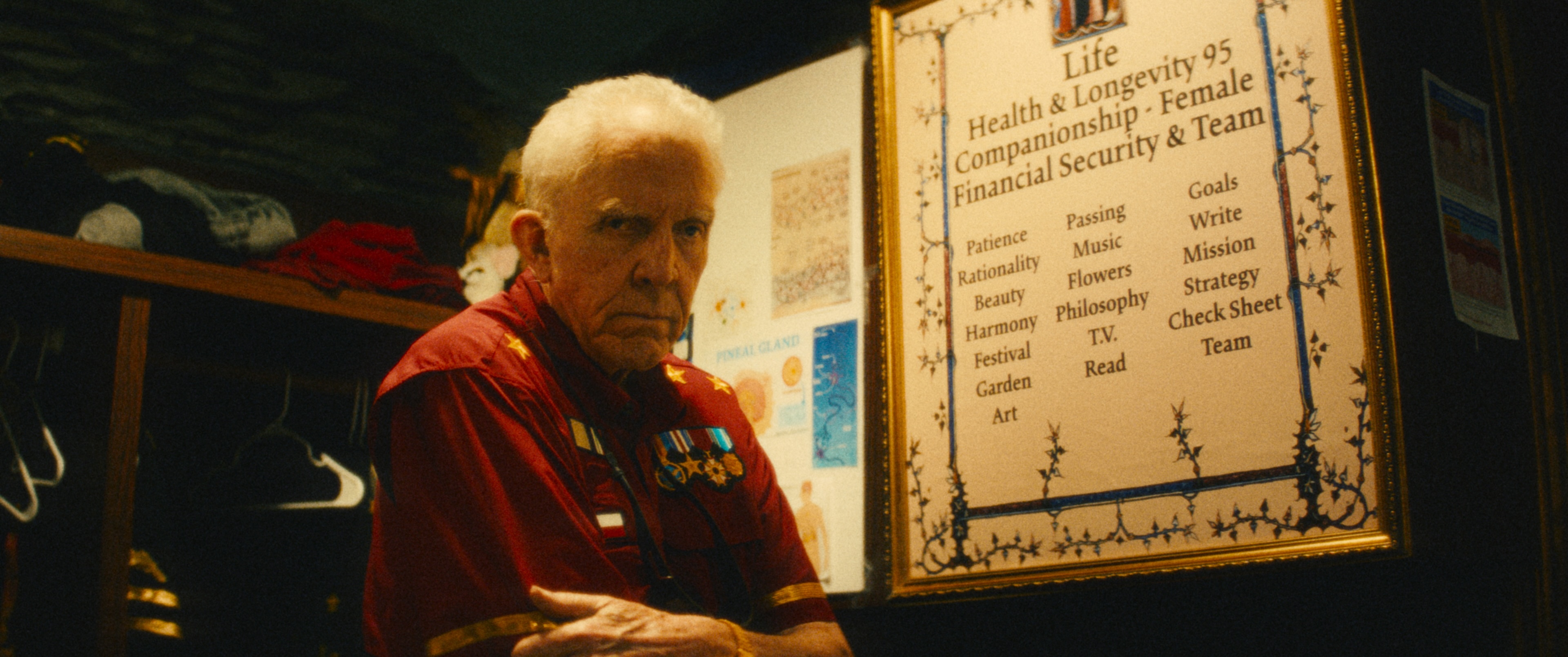

Lance’s style of storytelling and the setting of the documentary both heavily influenced the look for the series. Lance wanted to bring out the gold tones of George’s house to signal that he is not just playing a king, but truly different than everyone else around him, within his own regal setting.

King George describes his home as rococo or “overly decorated” and Lance extends that style to the look for the show. One way he accomplishes this is through what Lance describes as “God’s light,” for which Lance and Vandercruyssen share a mutual obsession, and which the duo brought out anytime the sunlight pours through the windows of George’s house. “You're almost in this purgatorial space between heaven and hell and it feels blindingly bright light every time that you're there with George,” he recounts.

“Working with Lance is always about exploring together and finding new ways to translate the vision for each specific world,” Colorist Damien Vandercruyssen notes. “A few principles usually emerge and become our guiding rules for that show. Ren Faire and King George allowed us to push the gold warmth and the ‘God’s light’ through halation and heavy diffusion. As often is the case with Lance, the look was approached from a texture perspective–this time mixing diffusion, lowering definition and adding grain to break the image.”

Beyond the scenes in Coulam’s home, the look evolves over the course of the series, “starting in a much more romantic, warm, magical place that conjured up all the positive associative feelings that the people in this series would have towards the fair, the place they gave their life to,” Lance notes, “But by the end, I knew that we would want to go somewhere colder and darker.” Vandercruyssen added that “the three-part series allowed us to explore a look that evolves through time, turning slightly more green and moodier towards the end of the show as the characters gradually lose their spark and magic.”

Lance notes as well that in the scenes that occur outside of George’s compound, say his dates at Olive Garden, the magic falls apart and the viewer is left with “this sort of mundaneness, like this nasty green hue that kind of comes in during those scenes. The God's light disappears. And he's just an elderly man.”

In addition to the look, Lance acknowledges that “the style of the show is almost rococo. There are talking Dragons. There are these magical flourishes that get you inside the headspace of what someone would be feeling, and they are over-directed and heavy handed, but still, there's this underlying truth to them, because the people in the images are going along with it and it represents exactly what they're going through.”

Toeing the Line of Docu & Narrative

“When I tell a story, it's all real, but there's also truth in reenactments,” Lance says regarding his methodology. “There's truth in acknowledging the absurdity of six or ten people in a room trying to capture real life. Invariably, that changes real life, and so if you push through the other side of the looking glass, you can capture a new kind of reality that only would have been created by your presence there.”

When it comes to revealing the truth of the subject matter, Lance adjusts his approach to best serve the world in front of him. Ren Faire was the director’s first time working with professional actors, and he had to accommodate the actors constant need for direction of some kind. He quickly realized that simply observing and shooting from a fly on the wall perspective would not work. So he leaned into the fact that he is working with a reenactment theme park featuring reenactors to “animate their desires.”

A film that is somewhere between narrative and documentary, Ren Faire forces us to see its subjects and the medium itself in a new way. By focusing on both the spectacle of the festival and the inner world of King George himself, Lance creates something that is both epic and intimate through unconventional storytelling methods and a conscious evolution of the look as the characters’ relationships change. The film is the latest installment in Lance Oppenheim’s exploration of how far the documentary genre can be pushed before it falls apart all together. So far, he has not found the ledge.