A CONVERSATION BETWEEN ALEX GIBNEY & TONY VOLANTE

Balancing Verité and Emotion in Documentary Sound

Interview by Ellie Powers

Documentarian Alex Gibney and sound mixer Tony Volante have been working together for almost two decades. The duo met in 2006 on the documentary, Herbie Hancock: Possibilities, which Alex produced. When I asked how they first met, Alex said, “I feel like I’ve always known Tony.”

The fact that Alex agreed to an interview at all speaks volumes about the rapport he shares with Tony, but more telling perhaps, was Alex’s choice of attire. Sure enough, Alex joined our call in a Harbor sweatshirt.

In Alex and Tony’s capable hands, sound guides audiences to better understand and sympathize with the story. In pursuit of truth, they carefully consider how to maintain emotional impact while striving for verité. The conversation delves into several of Alex’s films, offering a new perspective on Alex’s prolific filmography.

Alex and Tony reflect on the trust that fuels their partnership and begets the soundscapes for dozens of films. For music or sports, religion or corrupt billionaires, every subject requires its own delicate care to extricate truth from emotion.

Director Alex Gibney, Jigsaw Productions

Re-Recording Mixer Tony Volante, Harbor

Ellie: I'd love to hear about your working relationship and how your creative process has changed for sound, starting with your collaboration on Taxi to The Dark Side (2007), all the way to In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon (2023).

Alex: It's hard to say. It changes from movie to movie depending on what we're trying to accomplish. I've always valued Tony’s ability to create a soundscape that meets the creative intent of the movie and his ability to dig deep into the aesthetic and editorial aims of the film. Also, his ear, which becomes increasingly important to me as I get older and certain frequencies tend to disappear.

Tony: Right, one shoe doesn't fit all as each film has its own technique and style. But I think that the overview of the process probably hasn't changed all that much throughout the years. We attack them the same way and we’re used to adjusting our approach together to match a given film’s creative intent.

Taxi to the

Dark Side

Ellie: What role does sound plays in your documentaries or what role should sound play?

Alex: I like the idea that you can create a soundscape or a kind of a mood that may not always be utterly evident in a conscious way to the viewer or listener. Something you feel subconsciously. For example, in Taxi to the Dark Side, there was a plan to unite in visual space all the people who had been at the Bagram Air Force Base. We used the same backdrop and lighting scheme for the all the interviews, from New York to Birmingham where Moazzam Begg was. So, when it came to the soundscape, we worked hard to also create that feeling like you were really in Bagram, no matter where the interview was recorded. The whole idea was to create a purposefully realistic sound. Sometimes, you want to feel like it's the verité sound and you don't want to mess with it. Other times, you want to create a mood, a kind of a mindscape or a soundscape that takes you to a certain place. The intent was to create soundscapes that complimented the visual and enhance storytelling.

Ellie: Does the visual come first and then you're figuring out the sound? How intertwined are those two disciplines for you?

Alex: Sound is important from the get-go. I’ve been lucky enough to work with editors who are invested in sound and understand that. We make changes along the way, but a lot of the intent comes from there. Yet, documentaries are funny in that way, in the sense that they're like fiction films, but you write the script at the end instead of the beginning. As you hone the script and the structure of the film becomes more defined, you begin to see and hear things that become more evident. It’s a process of discovery.

In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon

Ellie: Are there any specific scenes or projects that stuck out for either of you as especially challenging or interesting mixes?

Tony: The whole process of sound for documentaries is challenging and interesting because there’s this fine line between enhancing the film, while making it still feel real and not overdone. You can't over sound design it to make it sound like a Hollywood movie. Yet, you want it to be cinematic and powerful enough. I think that's the real trick and the real mastery producing sound for documentaries.

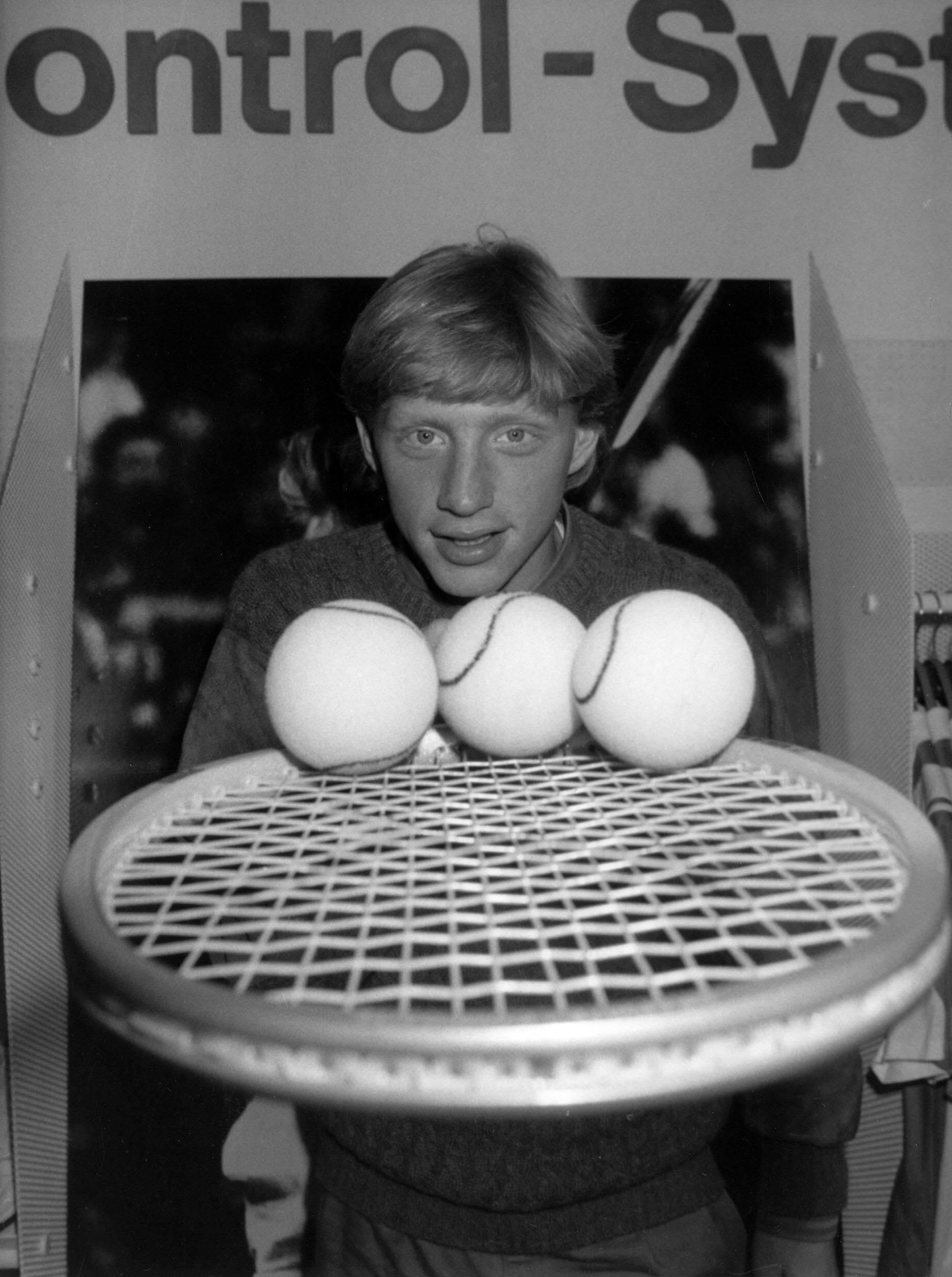

Alex: One example that was interesting in an unexpected way was our recent film Boom! Boom!: The World vs. Boris Becker. I had requested that the sound department pull together a bunch of different tennis ball sounds, depending on the era and the racket, and who was hitting and from where. That turns out to be tricky because you're creating a movie and it’s not just trying to represent reality. You're creating a moment and a lot of tennis is very psychological. There's also a rhythm to the game, and the sound of the ball contributes a lot to a sense of rhythm. But if you enhance it too much, it feels phony and over the top. If you enhance it too little, you don't get any of that emotion.

So, at what point do you lean into a sound and exaggerate it and other times pull it back? We made a choice to invest in those sounds, but to do so in a way that that really fit the character, the player, the rackets, and the psychology of any moment. It ended up contributing greatly to the narrative in ways that were unexpected.

Ellie: How do you approach incorporating silence into your documentaries?

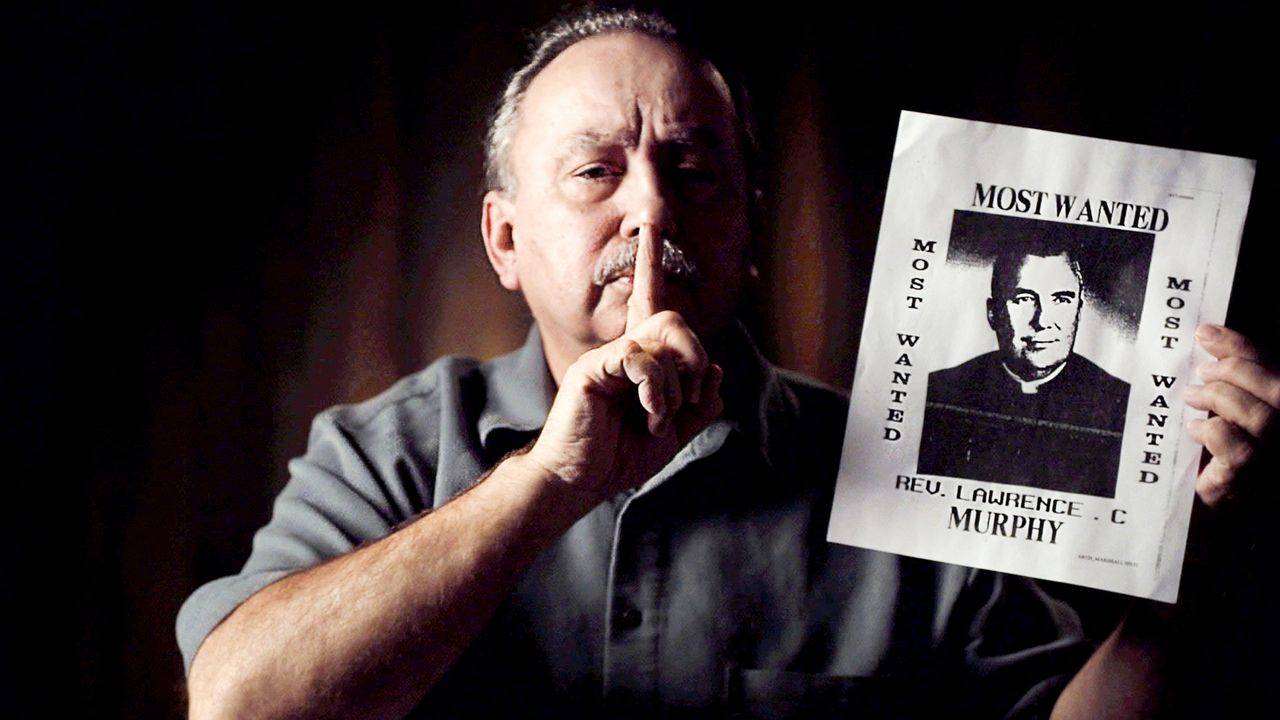

Alex: Super good question. Sometimes I think I should incorporate it more than I do, and my composers will agree. I recall we played with silence a lot in Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God. It's a film about deaf men and we didn't want to invest too much in the idea of what does a deaf person hear, but to really convey the idea that that there is a barrier between the hearing population and the deaf population. For some of our deaf heroes in the film, it was a little bit difficult for them to understand why we were mic-ing them, but we wanted to capture their hands, movements, some of their voicings. I remember we first introduced the main character of Mea Maxima Culpa, Terry Kohut, in a direct address interview. He was signing directly to camera but we intentionally left it raw and didn’t translate it so that you would have a sense of that gulf between the hearing and the non-hearing. If you didn't understand or recognize any American sign language, you wouldn't know what he was saying. We then translated what he had to say afterwards, as we went to imagery. That felt like a powerful sound choice. But as you mentioned, I'd like to investigate silence a little bit more in the future. It's disquieting.

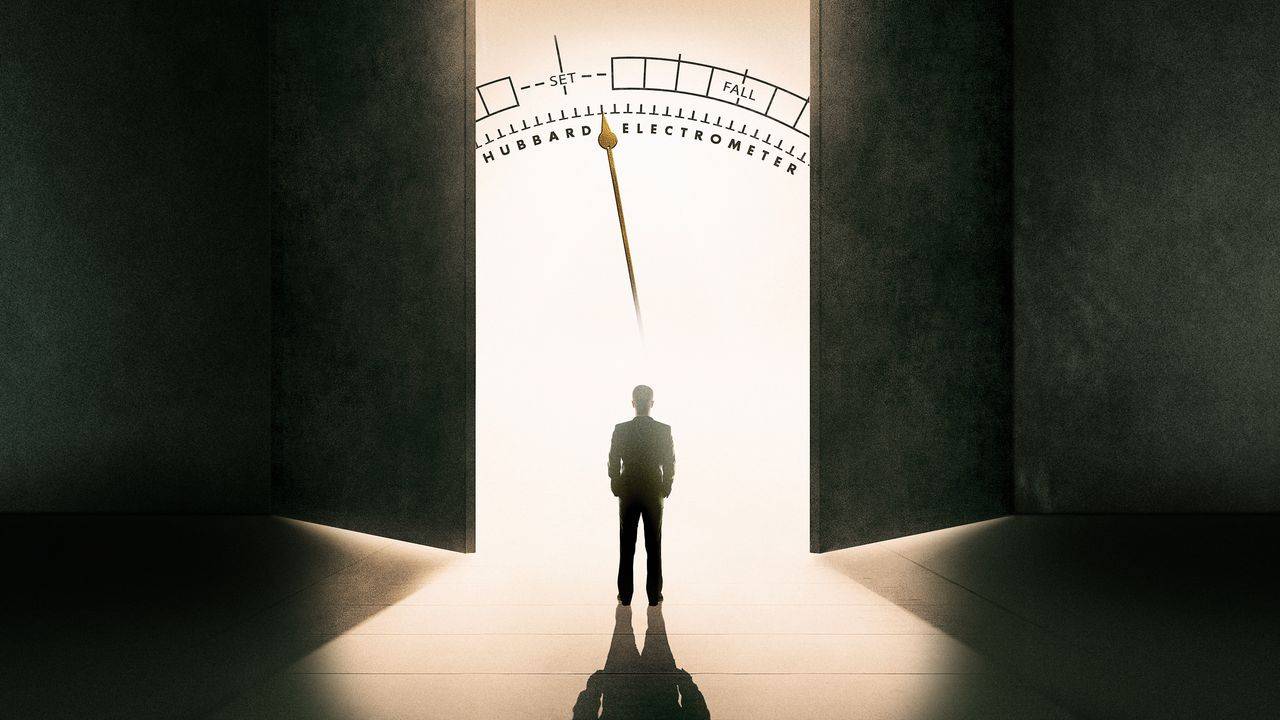

Tony: I think silence was used powerfully in Going Clear: Scientology & the Prison of Belief too. There were moments where we put in space to enhance some of the tension of them being questioned. Sometimes the silence, even a minute amount, makes a huge difference. It doesn't have to be several minutes of silence. It can be these brief little moments that let the film breathe.

Alex: And sometimes we consciously leave them. But sometimes in interviews themselves, silence can be super important. You’d be surprised how much more people tend to offer when they feel that uncomfortable silence that everybody seems to have a need to fill, but you can't get there without feeling that uncomfortable silence.

Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God

Ellie: Let’s talk about your most recent collaboration: In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon. How did you approach the sound and blending music into the soundscape?

Alex: I wanted to find a way, particularly in some of the present-day performances in Paul’s studio, whether it be in Austin or New York, to maintain that intimate off-the-cuff sound while preserving enough of an allegiance to the final record. It was important to feel both.

We had all these great performances from Paul throughout the years. So, we tried to deliver to Tony as much of the multitracks as we could. That way he could really work his magic and give them the sort of richness they deserve. We knew from the beginning that we were going to let some of this music play at length. And if you're going to do that, you have to commit to a richness of sound that's going to take the viewer someplace special. Because that’s what music does. It takes you someplace special.

Tony: It's always particularly fun with Alex when we mix music together. I might do an initial pass on some of the music, but Alex and I really get the creative juices flowing when we start mixing together and making choices –pulling some stems, maybe moving some music around. We always end up discovering pleasant surprises during the mix.

Ellie: Alex, can you tell us a bit about your process for archival sound specifically and how you weave that into the narrative?

Alex: Again, I would say it kind of depends on the film or even a given scene. There are times you might feel motivated to make it breathe as if it's real and compromise or silence the sound. Other times, you might want to emphasize that the archival is kind of a memory or almost a dream, and don't really want to recreate sound as if it's real.

Crazy, Not Insane comes to mind. Rather than lean into the actual sound of the archive, we chose to take it to a very dreamlike place. We used pieces of archive that weren't necessarily related to the subject at hand but incorporated them to create dreamscapes. So, it was intended to connect you unconsciously and give you a feeling of almost free associating. This is really where Tony, sound editor Dan Timmons, sound designer Bill Chesley, and I work together to determine what sounds should be rigorously real and key to the to the archive and what sounds should have a kind of more dreamlike or metaphorical vibe. And that is a more intuitive process.

Tony: I'm enjoying listening to you talk. I think you're nailing everything, and I’m also learning. I also see the archival layer like a movie within itself. The archival has been produced and a lot of it has elements you can't revise. So, you're taking that layer and either playing it as it is, just as it was intended to be from the original source, or manipulating it in a way that it becomes a sound design element. That also comes in various shapes and forms of quality that we have to deal with, so it can be challenging.

Crazy, Not Insane

Boom! Boom!:

The World vs. Boris Becker

Ellie: Speaking of – Wish to say anything else to fill this uncomfortable silence?

Tony: Just, thanks to Alex. This has been great. Your loyalty has meant so much to me over the years. There’s a lot of it in the business and for a reason. It pays off. Once you have that trust with someone, it just opens the creative process up that much more.

Alex: Right. I trust you to go through and do those first passes that I don't really have to be there for. So, working together for so long has allowed us to focus on the creative challenges of the film when we get together.

Tony: Well, looking forward to the next one.

Alex: Me too.

Harbor extends its heartfelt gratitude to the prolific Alex Gibney and Jigsaw Productions for their unwavering support and loyalty. It's a privilege to collaborate with such a visionary filmmaker, and we are deeply grateful to Alex for generously sharing his time and invaluable insights with us.

Going Clear: Scientology & the Prison of Belief